High-tech tools make management techniques possible that keep crop production at Rulon Enterprises efficient and cost-effective.

By Martha Mintz, Contributing Writer

Remember the simple days when high-tech in the field meant having a tractor with air conditioning and a radio? Today, cabs are positively teeming with technology.

There are gadgets that monitor, record, adjust, beam information to and from satellites — why, they'll even drive the tractor for you if you want.

Technologies both in and out of the cab are helping today's producers make a more precise science of crop production. Using those technologies correctly can pay in higher yields, greater efficiencies and more cost-effective and environmentally responsible agriculture, Arcadia, Ind., no-tiller Rodney Rulon told attendees at the National No-Tillage Conference.

Rulon no-tills 5,200 acres of corn and soybeans with his cousins, Ken and Roy. They use precision techniques to gather data for determining everything from where drainage is needed to seeding rates.

"The bottom line is that knowledge is power," Rulon exclaims. "Precision farming is the best set of tools for managing inputs with conservation and economics in mind.

"Using precision practices, we've increased our efficiency. We're getting more done faster and doing a better job at the same time."

1. Yield Maps

"This is where we all got our start in precision farming," Rulon says. "The problem is that the information from yield maps often is underutilized because it's not a soil test or something that’s really easy to interpret."

He says that yield maps are great for printing out and determining where tile is needed, but ultimately they serve as a report card for your farm.

|

"They’re great for doing strip tests, keeping track of side-by-side data and yield histories. You can use them to illustrate your point when you negotiate with landlords about why the farm isn’t as good as they think it is, or to explain to them why they’re getting that bonus," Rulon says.

They also help producers monitor the success of various inputs.

"Nutrient removal and replacement, planting improvements, all those decisions can be made by being able to go back and look at that report card and move forward from there," Rulon says.

But the data has to be good for it to be useful. Rulon warns that producers need to make sure that they — and everyone else helping with harvest — keep the yield monitor calibrated and online at all times.

When there’s more than one combine working in a field, he says to be sure they’re calibrated the same to we’ve seen, the real value is in getting gather the best data.

2. Soil Sampling

"Soil sampling is one of the first things we did using precision and it’s still one of the most valuable things that we do," Rulon says.

The Rulons sample using 1-acre grids. He drives to the center of the grid and then takes six probes in a 30-foot circle from the center. In that manner, he’s covering a 60-foot circle in the center of a 200-foot grid.

"To make this work, we’ve stretched out sampling to every 4 years," Rulon says. "But from what we’ve seen, the real value is in getting that intense data.

"There’s a lot of variability at work in fields from contours to old fencelines and other unknown factors. That’s why rather than using management zones and skewing data by what we think is happening, we went with the 1-acre grid. It’s a decent representation, which gives me resolution and resolution equals value."

With precision soil tests, Rulon is able to use data from soil samples to manage more than just spreading fertilizer and controlling phosphorus and potassium expenses.

"We’re using this for input management, planting and making farm-specific recommendations," Rulon says. "We’re trying to manage the productivity of the farm and the health and balance of the soil at the same time."

3. Variable-Rate Applications

The Rulons use data from soil tests and yield maps to determine variable rates for a number of inputs, including lime, gypsum, phosphorus, potassium, nitrogen, seeding rates, insecticides, herbicides and manure.

|

"Lime was our biggest value when we tried variable rate 15 years ago and it’s still our No. 1 value," Rulon says. "It pays dividends. We make money where we don’t put lime and we make money where we do put lime."

Determining where lime is needed goes back to the 1-acre grid soil samples. Rulon looks at organic matter and magnesium content to determine need.

After years of careful lime placement, they now average about three-quarter ton to the acre every fourth year to maintain a pH of 6.4.

"We also use variable rate for gypsum, composted municipal waste product and sludge," Rulon says. "There are specific reasons that you want to use each of those and you should know enough about the products to know where it works best and where you need it the most.

"By the time you factor in trucking, we’re looking at about $25 per ton products, so we don’t want to just throw them out there with no justification."

Rulon goes back to the yield maps to evaluate the inputs and plan future applications.

"About 60% of our soils haven’t shown a response to gypsum, but 40% of our soils had a very nice response. We don’t want to waste $25 per acre on the 60% that don’t respond," Rulon says.

4. RTK And Guidance

Back in 2003, Rulon was using a lightbar to guide soybean planting and to spray accurately. He thought he did a pretty good job manning the steering wheel himself. But once the Rulons started using a real-time kinematic (RTK) system that allows correction of GPS signals for accuracy within a centimeter, he let the tractor do the driving.

"We thought we were doing pretty well, but it turns out the computer was better," Rulon says. "There’s no more overlap, which is what starts to pay for the system. Plus, we have increased productivity.

"It reduces fatigue, so we’re definitely getting more done in the day and can still get up and do it again the next day." The Rulons do some strip-tillage and have seen RTK and auto-steer really pay off on those acres.

"We’re running strip-till with a 13-shank sidedress bar and coming back with a 24-row planter. You can’t do that very easily any other way but with RTK," Rulon says. "It works flawlessly all the way across the field.

"And it gives us flexibility in our equipment. We don’t need a 24-row strip-till bar to match a 24-row planter to match a 24-shank sidedress bar."

Auto-steer also pays at soybean harvest.

"With auto-steer, you spend your time looking at the head, setting the combine right and making sure that everything is feeding and working instead of trying to peer through a cloud of dust to make sure the end of the combine is in the right place," Rulon says. "You pick up ground speed because you’re able to concentrate on what you’re doing and you do a much better job of harvesting."

5. Seeding Accuracy

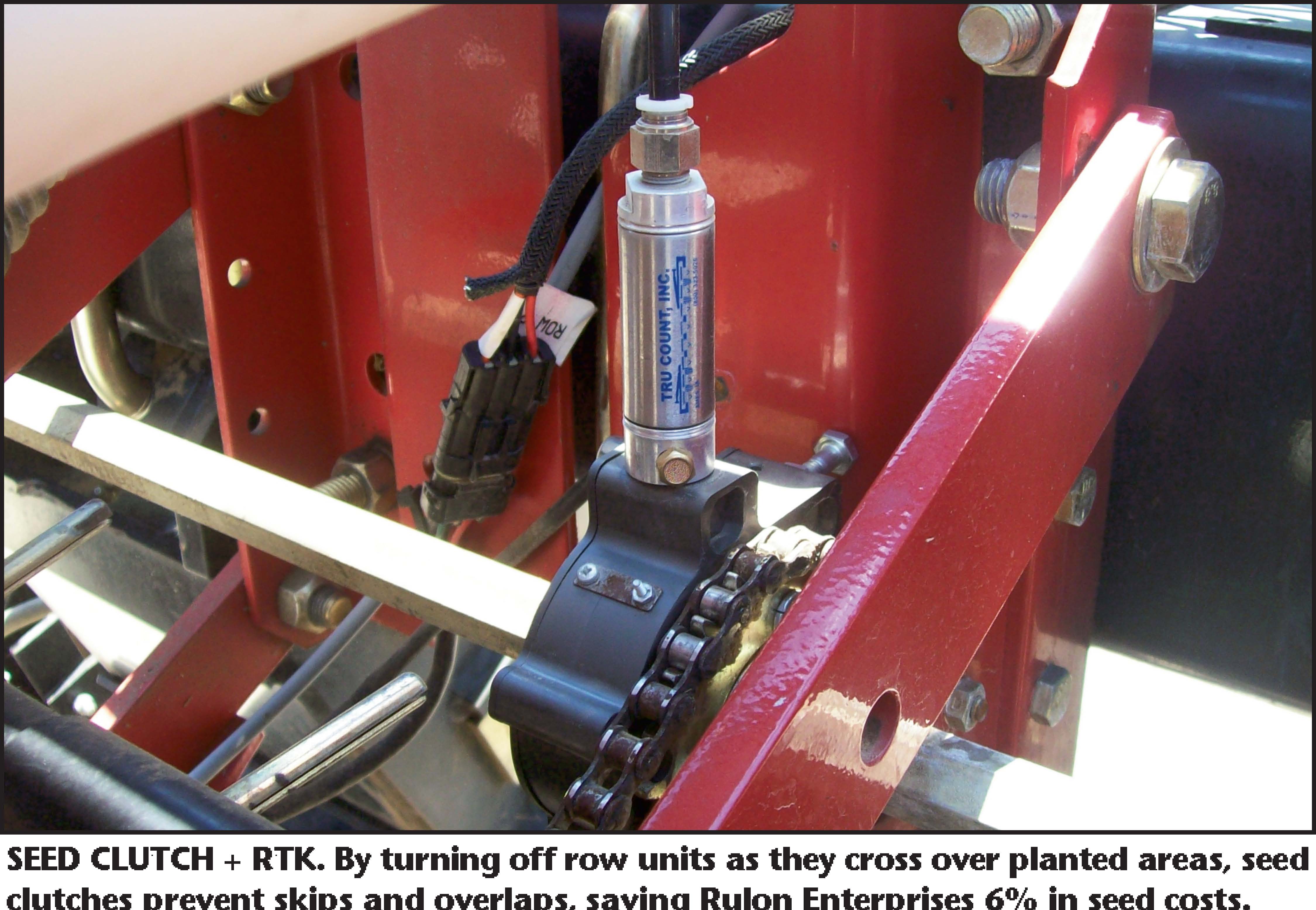

With RTK, Rulon also suggests installing a seed clutch system. "Seed clutches are something I would encourage anybody that’s got the RTK equipment to use because they just pay and pay and pay," Rulon says.

Seed clutches work with the guidance system to engage and disengage row units to avoid overlap or skips. Systems can be set to shut off individual row units or sections of row units when the system senses that a unit has crossed over a planted area.

"On 2,600 acres of corn, we save about 6% on seed by eliminating overlap on the ends or the angles or anywhere else. When you’re paying $200 to $300 per bag of seed, that really adds up," Rulon says. "We’re paying for that system every year in seed savings and that’s not allowing anything for increased yield.

"You’ve got 6% of your acres somewhere that would have been double-planted without the system; and we know what that does to yield. A seed clutch system pays for itself and then some."

Rulon also suggests using the RTK system to gather topographic data.

"With RTK surveys, gathering topographic data is quick, cheap, easy and anybody can do it," Rulon says. "You can feed the data into GIS to make topographic models, which you can use to look at your watersheds, decide where to lay tile, do cost estimates and more."

6. Boom Section Control

Just like with the seed clutch, being able to shut off sections of their sprayer allows the Rulons to avoid overlaps, saving cash and nipping crop injury in the bud.

"We’ve got a 100-foot boom with 10 sections that we can turn on and off individually," Rulon says. "It saves us a lot of chemical, a lot of hassle and misapplication."

7. Remote Sensing

"We’ve tried this in the past, but we’re not actively using it now," Rulon says. "We started trying it with Resource 21 back in the mid1990s and we liked what it did, but you have to hit that price, value and timing combination for your farm for it to be economical.

"As prices come down, it certainly is a good thing to consider."

8. Soil Electrical Conductivity

This test provides producers with information on soil texture, cation exchange capacity (CEC), drainage conditions, organic-matter level, salinity and subsoil characteristics.

"If I didn’t have 1-acre grids, this would be something that I would look at seriously," Rulon says. "If you’re looking at the best ways to define your farm in management areas, then this works pretty good. We’ve done it in several of our fields, but on the larger scale, it’s been easier in our situation to just stick with the 1-acre grid system."

According to Virginia Cooperative Extension, EC maps can be paired with yield maps to possibly explain yield variations, create management zones and much more.

"There are a lot of ways to use precision and a lot of gains can be made," Rulon says. "But it’s not cheap, it’s not easy and you have to use the data once you collect it.

"A lot of people get excited by yield data on the card and soil test data, but you’ve got to pull that together if you want to use it and get value out of it."

And, Rulon says, no-tillers stand to benefit from the technology.

"No-till isn’t easy, but precision data can help overcome some of the challenges," Rulon says. "It’s helped us to do a better job on our farm."

Editor's Note: This article appeared on page 62 of the May 2009 issue of No-Till Farmer Conservation Tillage Guide.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment