From auto-steer to hydraulic down force on planters to variable rate application, precision technology is an integral part of most modern no-till operations. Since the early days of no-till, a practice that began commercially in the U.S. in 1962, this group of farmers has embraced and found success with precision agriculture.

“Is there a relationship between precision farming tools and no-till? Absolutely,” says Clay Mitchell, a fifth-generation Iowa farmer and co-founder of Fall Line Capital, a farmland venture capital firm.

Mitchell was an early adopter of precision technology. He used autosteer in 2000 to strip-till between old corn rows to plant corn on corn, making him one of the first people in the Midwest — if not the U.S. — to farm with auto-steer.

Scott Shearer, chair of the department of food, agricultural and biological engineering at Ohio State University, started working with Kentucky no-tiller Mike Ellis in 1994 to adopt precision ag practices in no-till farming. Ellis, who no-tilled for about 40 years before retiring, taught Shearer about the innovative practice.

A Rantizo drone, 1 of 3 in the swarm, conducts a water trial to demonstrate how drones can efficiently apply chemistry to fields. From spraying to scouting, experts see great potential for drones as a practical autonomous solution for no-tillers.

“By their very nature, no-tillers have to be creative people,” Shearer says, “and my experience tells me they were some of the first adopters of a lot of precision ag practices.”

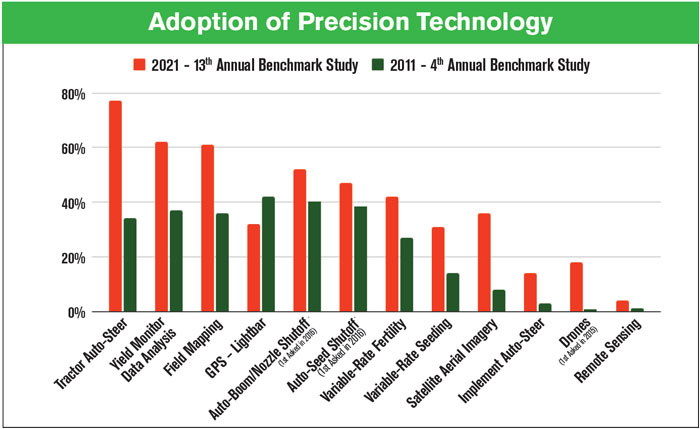

Over the last 10 years, adoption of precision technology by no-till farmers has increased in most uses. This chart compares adoption rates from the most recent No-Till Farmer Annual Benchmark Study, conducted in 2021, and the publication’s 4th Annual Benchmark Study, conducted in 2011.

John Fulton, a professor and extension specialist at Ohio State University who focuses on precision agriculture and machinery automation, agrees technology has enabled no-tillers to run more efficient and successful operations.

Down force technology has improved seed placement for no-tillers. This technology helps keep down force on the planter row units even if soil and residue conditions vary across fields. It also minimizes bouncing, keeping seeding depth more consistent.

Autonomy in Agriculture: A Timeline

2008 – John Deere Concept iTEC (Intelligent Total Equipment Control) Pro

2011 – Fendt/Trimble Guide Connect Driverless Tractor

2013 – Kinze Autonomous Grain Cart

2016 – CNH Autonomous Project

2018 – DOT (now part of Raven) Debut

2018 – Yanmar Robot Tractors

2019 – Sabanto Ag Custom Planting Project

2020 – Raven AutoCart

2022 – John Deere Autonomous 8R Tractor

Source: Bill Lehmkuhl, Precision Agri Services, Minster, Ohio

RTK auto guidance allows the Ohio no-tillers Fulton works with to plant soybeans in 15-inch rows right next to where the 30-inch corn rows had been. The row units aren’t running over the previous year’s corn stalks and root balls, thereby creating a better seedbed.

Automatic section control, variable rate application of fertilizers and yield monitors have also improved no-tillers’ success in the last decade. Both the automatic section control and variable rate application of fertilizers save on inputs, and yield monitors are conducive for on-farm research.

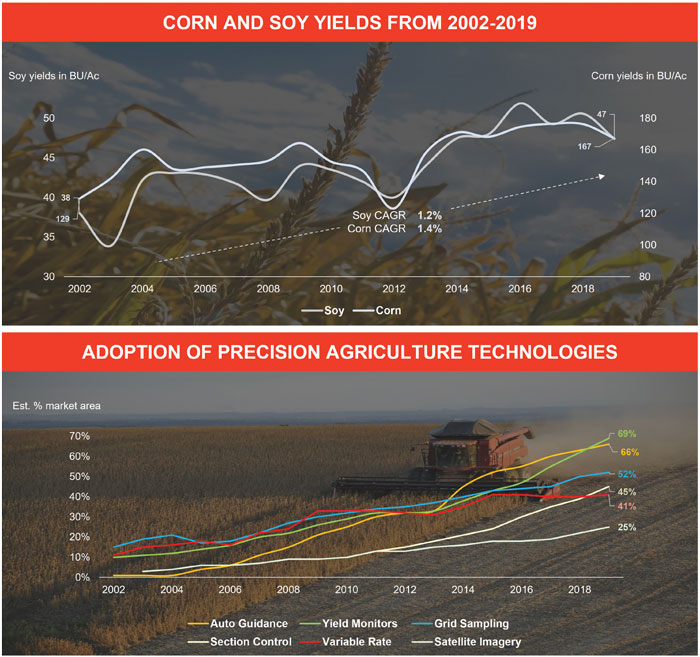

Growth in corn and soybean yields over the last 18 years coincides with adoption of precision technology, as shown in these two charts from the Environmental Benefits of Precision Agriculture study released in February 2021.

Fulton and Shearer believe precision planter technology is advancing — and will continue to advance — no-till farming. These tools enable no-tillers to get better stand establishment early in the growing season and determine the best down force as they move across the field. Fulton says emerging technology like Precision Planting’s SmartFirmer — a seed firmer sensor that measures organic matter, temperature, soil moisture and more — will make a significant impact on no-tilling.

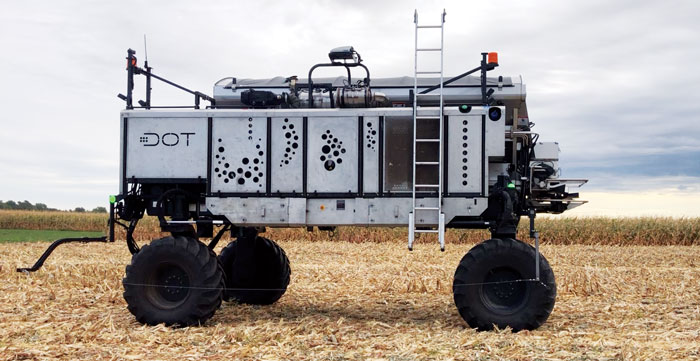

DOT, now known as OMNiPOWER after acquisition by Raven, is an autonomous power unit that couples with implements to drive itself and perform farming functions. It first debuted in 2018.

“As a no-tiller, I could have quite a bit of residue on the surface, and those sensors that run in the furrow can be insightful about soil conditions during planting,” Fulton says.

Mitchell and Fulton see great potential for drones as a practical autonomous solution for no-tillers. Drones equipped with high-tech cameras and artificial intelligence (AI) can scout and provide feedback data about stand counts, crop health and more. Autonomous drone spraying systems offer precision control without compaction or crop damage.

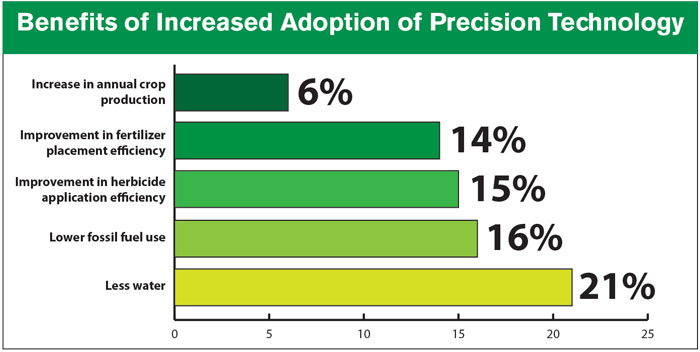

Making precision agriculture technologies widely available is good for the environment and farmers, according to the Environmental Benefits of Precision Agriculture study by the Assn. of Equipment Manufacturers, the American Soybean Assn., CropLife America and National Corn Growers Assn. This chart illustrates the potential benefits of growers using more precision ag technology.

“This is a new technology that’s available today, and we’re starting to see farmers think about using that kind of technology and the value it could provide,” Fulton says.

Some of the majorline manufacturers are already investing in technology to selectively apply herbicides in what Shearer calls “micro sprays.” Sprayers equipped with AI can detect weeds among growing crops and apply herbicides only to the weeds. Shearer says this selective application could reduce herbicide costs by as much as 80%.

Will No-Tillers Embrace Autonomy?

We asked three precision farming experts about the impact autonomy will have on no-till and if no-tillers will be at the forefront of autonomous adoption, as they have been with other technologies over the decades.

John Fulton predicts autonomous machinery will become more common in the next 2-3 years.

“For no-tillers, the more you minimize passes across the field and have control of that, the more improvements you’re going to make with compaction and soil health,” Fulton says.

Autonomous machinery will likely become smaller and lighter as it advances, providing more of those compaction-reducing benefits. Scott Shearer believes that’s what will drive no-tillers’ adoption of autonomous equipment. Then, rather than sitting on the equipment as it moves through the field, the operator will be off site monitoring the machine.

“Pretty quickly that will expand to as many as 10 machines,” Shearer says. “That’s where the value comes in for going to fully autonomous equipment. We’ll have experts monitoring that equipment, ensuring it’s performing its function.”

Both Shearer and Fulton note the potential of autonomous equipment to alleviate labor shortages, especially for tasks requiring technical expertise. Shearer says Sabanto Ag and other companies currently offering autonomous technology are also providing “Farming as a Service,” in which farmers pay a per-acre fee to have the company’s trained staff run the equipment on their fields.

Clay Mitchell says whether no-tillers are early adopters of autonomous equipment will depend on the type of machine.

“Full autonomy is pretty challenging for ground-engaging devices,” Mitchell says. “At this point, taking somebody out of the cab is not a step forward in most

cropping operations.”

The cost of an operator pales in comparison to the cost of a $1 million combine and wages for laborers pulling weeds in specialty crop fields. More importantly, the operator is able to perceive and adjust in a way autonomous machines can’t at this point, Mitchell says. A person can spot a muddy area in the field, recall that they got stuck there last year and make adjustments.

“Not only does the machine not have that context, it doesn’t have the history or awareness of the field that a person would have,” Mitchell says. “They’re so far away from even beginning to think about solving problems like that.”