The development of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and associated ag-specific software programs have made aerial imaging of farms more useful and accessible than ever before.

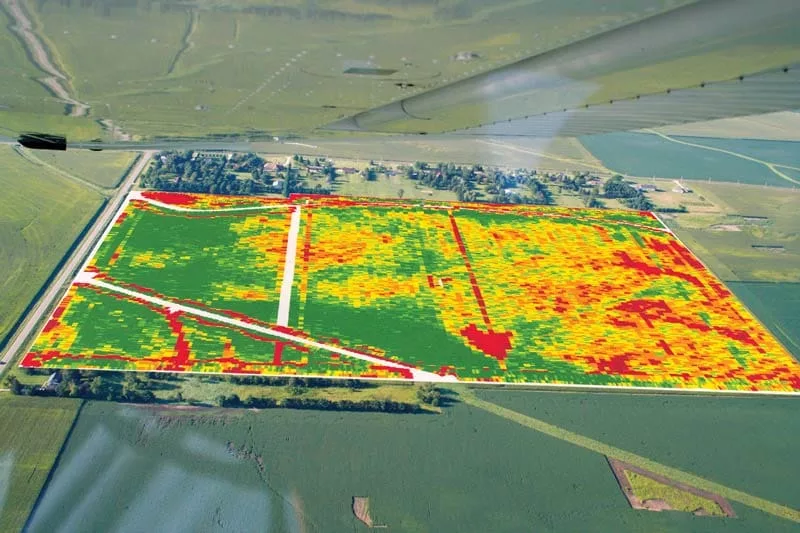

With the ever-improving quality of digital cameras, not only can service providers capture regular images of farmland, but they can also get multi-spectral images that provide information about plant health, soil health, plant population, water infiltration, pest outbreaks and more.

Additionally, software programs can “stitch” the images together to form a comprehensive view of large areas that can be loaded into yield-mapping software and layered for additional insights.

Bob Recker, owner of Waterloo, Iowa-based Cedar Valley Innovation and a retired engineer from John Deere, says it’s important to first “think about the why” of using UAVs. Recker started doing aerial farm imagery in 2008 as a passenger in an airplane with a window that opened.

He had a simple SLR camera with a zoom lens and would simply point the camera out the window and shoot images. When drones were introduced, he started experimenting right away and over time have developed these tips for growers interested in getting started with UAVs.

Recker shares these 20 tips for capturing the most practical value when taking flight with UAVs.

- Before you do anything else, think about why you want to get started with imagery. It must go beyond wanting to play with a drone or see a farm from above. Ultimately, you’re trying to make money and the drone is a tool to help you achieve that.

- The cheapest part of the system is the drone itself. You’ll spend a lot of time on the software side, which itself will probably be service based and, therefore, an ongoing expense. Currently, a decent drone is about $1,200 and a service like Drone Deploy costs about $100 per month, so the service you provide needs to make the drone worthwhile and could cost the same as the drone itself.

- Aerial imaging is a good way to get visibility in your customers’ fields. More than anything else, it offers a way to detect problems in their fields, ideally earlier than they would know about them otherwise.

“The best images aren’t worth anything if you don’t go out to the fields to see what’s going on. Ground-truthing matters…”

— Bob Recker

Unfortunately, most problems can’t be fixed right away — most likely they will be issues farmers have to address in the following season and some, like wind events, can’t be addressed at all. But with imaging, there will be fewer surprises at harvest because they already know about a lot of the problems they will have encountered during the growing season.

- Rule of thumb: If you can see a problem from the air, there will be a yield impact and it’s usually a negative impact — even if it doesn’t later show up on a yield map.

- When you see a straight line in a field, it is a manmade or equipment problem. Curved lines represent nature — problems with soil, topography or wind. Typical manmade problems that you can see from the air include when an anhydrous tank ran low, the center of the planter was lighter than the ends, or if there is too much or too little tile in an area.

- The best images aren’t worth anything if you don’t follow up by going out to the fields to see what’s going on: Ground-truthing matters.

- The best time of day to fly is 15-20 minutes after sunrise because you get long shadows. If a corn plant is starving, has been injured or is missing, it shows up as a really dark spot because it’s a shadow. At high noon, you might not see it at all.

- Don’t fly when it’s cloudy — you can’t tell if what shows up on an image is a soil issue or a light issue. Also, a good time to fly during the growing cycle is when the plants canopy — before that all you see is soil.

- Make sure to get reference points. When you see something interesting, zoom in close to shoot the detail but then quickly back out for an overall shot that will include a point of reference like a road, a waterway or a building.

- You must have an FAA license to fly a drone as part of a commercial operation. This is like a light version of a pilot’s license.

- It’s illegal to fly a drone above 400 feet. 275 feet is pretty good for most field imagery.

- Use programmed flight paths. Set up a flight path and store it. This will give you the ability to fly that same pattern over and over and then overlay the images to see how things change over time. But with each flight, be sure to program “home” where you start the flight, not where it was before.

To illustrate the point: A friend of mine, when he first got a drone, turned it on and put it on the kitchen table to look at it. He later took it out and flew it and then, after a while, presses the “home” button and ‘Bam!’ It flew right into the side of the house. It thought “home” was on the kitchen table. - Get familiar with multi-spectral imagery. Sometimes called NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) or NDRE (Normalized Difference Red Edge Index), this technology measures the light from frequencies beyond the visible range and will give you surprising insights into what is going on in your customers’ fields.

- Get familiar with Google Earth. If you have Google Earth Pro, you can view a location over time by selecting “Historical Imagery” under the “View” tab. This will allow you to look at older images of your land. Different years may show your fields at different times of the year. Some imagery is public domain, so you can download it.

- Getting stitched images is key (about 1 picture per acre) because it gives you an overall view of a field.

- Understand that these files can be huge so uploading can take a long time. Don’t expect to have these files uploaded from the field. Plus, you need to have to have a good computer to view them.

- Bottom line: If you aren’t willing to go out and get dirty and figure out what’s going on, don’t bother. Information that you don’t act on is worthless, it’s just wall art.

Validating the Value of UAVs as an Operational Tool

With the ever-improving quality of digital cameras, not only can no-tillers capture regular images of farmland but they can also get multi-spectral images that provide information about plant health, soil health, plant population, water infiltration, pest outbreaks and more.

No longer are Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) considered farm toys as they develop into decision-making tools, thanks in part to advanced software programs that can stitch images together to form a comprehensive view of large areas then uploaded into yield-mapping software and layered for additional insights.

“We’re evolving from a farmer buying a DJI drone from Best Buy and adding a camera to take pictures because it’s fun, to having UAV systems become a real part of farm operations,” says Mark Dufau, director of business development for AeroVironment, which manufacturers the Quantix hybrid drone ecosystem.

Dufau suggests one of the most significant impacts UAV technology has had is with fertilizer application verification, with farmers able to aerially scout, identify and treat trouble spots during the growing season, in an efficient, effective way. The Quantix system can cover 400 acres in 45 minutes, a more timely alternative than visually scouting fields on foot.

“We had a farmer with a center pivot system that was creating rainbow effect on the inside of that pivot and they had set the wrong fertigation rates which were creating bands of infertility and heavy fertility on those inside parts of their pivot,” Dufau says. “The farmer was able to identify the problem and go out and make those adjustments.”

Even though UAV technology has become more sophisticated, systems have become more automated, making them easier to operate and more tailored, with packages designed for individual producers, or scaled to meet the business needs of precision service providers.

But prior to getting serious about investing in a system, Dufau recommends that farmers get their Part 107 Remote Pilot Certification, which is a relatively easy process.

“It had been viewed as a big hurdle because farmers didn’t want to have to go get a pilot’s license,” he says. “In reality, it’s a 60-question multiple choice test that can be taken at your local airport. The certification is a requirement from the Federal Aviation

Administration for anyone flying a drone commercially, which includes farmers, and covers the regulations, operating requirements and procedures for safely flying drones.”