During a farm and ranch management course at South Dakota State University, students were asked, “How many of you grew up on a farm?” About a third of the class raised their hands. When they were then asked, “How many of you plan to return to the family farm after graduation?” most students kept their hands raised, and some who did not have a farming background also raised their hands. More students than expected expressed plans to become farmers after completing their degrees. This glimpse comes from a single class in South Dakota, but it might be the flap of a butterfly’s wings, heralding a bright future for U.S. agriculture.

This small glimpse appears to align with a broader trend across the United States, as reported in the 2012, 2017, and 2022 Census of Agriculture. The Census of Agriculture defines new and beginning producers as individuals who either have not previously operated a farm or ranch or have operated a farm or ranch for no more than 10 years. The total number of agricultural producers increased from 3.18 million in 2012 to 3.40 million in 2017 before declining slightly to 3.37 million in 2022. Among them, the number of new and beginning producers rose from 552,058 in 2012 to 908,274 in 2017, reaching 1,011,715 in 2022. Their share of the total producer population has been steadily increasing, rising from 26% in 2012 to 30% in 2022.

Despite the increase in the number of new and beginning producers, the aging of U.S. agricultural producers appears to remain a persistent concern. The average producer age was 58.3 years in 2012, declined slightly to 57.5 years in 2017, and increased again to 58.1 years in 2022. As Katchova and Sun (2024) showed, the average age of new and beginning producers in 2022 is 47.1 years, which challenges the common belief that most new entrants into farming are in their 20s or 30s. The Census of Agriculture defines young producers as individuals aged 35 or younger and reports corresponding statistics. From 2012 to 2022, the number of young producers exhibited minimal change,accounting for 8.1% of all U.S. producers in 2012, 8.4% in 2017, and 8.8% in 2022. Likewise, among new and beginning producers, young producers consistently comprised only 24%–26 %.

Precision agriculture (PA) technologies are gradually being adopted and utilized on U.S. farms to enhance operational efficiency and reduce the need for manual labor. These technologies not only decrease the time and physical effort required to operate farms but also improve profitability through more efficient input use (Genius, Pantzios, and Tzouvelekas, 2006; Schimmelpfennig and Ebel, 2016; DeLay, Thompson, and Mintert, 2022). New and beginning producers currently rely on off-farm income for 77% of their total household income (Key and Lyons, 2019), and more than half work off the farm for over 200 days per year (Katchova and Sun, 2024). While such reliance may improve their financial stability, it also indicates limited time available for farm operations. By automating key tasks, PA technologies save time and reduce labor requirement on the farms, helping farmers maintain their operations with limited time and physical effort.

PA technologies also have the potential to address financial instability, a major challenge for new and beginning producers. Even individuals who grew up on family farms often hesitate to take over or start their own operations, viewing farming as financially uncertain and less rewarding than other career options (Haws, Just, and Price, 2025). By increasing efficiency and potentially boosting profitability, PA adoption can strengthen the long-term viability of these producers and support the entry and retention of the next generation of farmers.

Ofori, Griffin, and Yeager (2020) showed that younger farmers tend to adopt PA technologies sooner than older generations. On the other hand, Kolady et al. (2021) found that more years of farming experience increased the likelihood of adopting PA technologies, while age had a negative effect. These seemingly conflicting results may be due to the correlation between age and farming experience, which makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of the two.

Therefore, it is important to examine how the perception and adoption of PA technologies vary across farmer groups, considering both age and farming experience. This study places particular emphasis on “farm kids” who grew up on a family farm. Some of these young producers began operating farms immediately after graduating from high school or college and have accumulated more than a decade of farming experience. Although they are still considered young, they no longer fall under the category of new and beginning producers. Understanding how these young but experienced producers perceive the need for PA technologies is important for identifying trends in PA technology adoption among the next generation of farmers and informing future support strategies. Their perspectives may offer unique insights into how early exposure to farming influences technology adoption decisions over time.

Survey Description

We conducted a mail survey in North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Nebraska to understand PA adoption status, profitability, and future adoption likelihood, and farmers’ perceptions toward precision technology. Our survey was conducted from July to September 2021 using farmer mailing addresses purchased from Dynata (dynata.com). The survey was mailed to 1,500 randomly selected farmers in each state, with the screening criterion that each farmer operated at least 100 corn acres. We contacted the 6,000 farmers up to four times based on the modified tailored design method (Dillman, Smyth, and Christian, 2014). First, we sent an advance letter providing a link to access the survey online. Next, we mailed the first copy of paper questionnaire with prepaid return envelopes to producers who did not respond during the first wave. A reminder/thank you postcard was sent in the third wave, followed by a second copy of the paper survey in the fourth wave (Wang, Jin, and Sieverding, 2023). We received 1,119 responses out of 5,473 eligible addresses, indicating a response rate of 20.4%, which is comparable with other published studies that surveyed agricultural producers using generic databases (Fielding et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020).

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics comparing the questionnaire responses related to adoption rates, likelihood of future use, and profitability perceptions of PA technologies among different farmer groups. We categorized survey respondents into four groups based on their ages and years of farm operating experience: senior established, young established, senior beginner, and young beginner. Note that young and senior producers are distinguished based on age, using 35 years as a threshold; while beginning and established are classified by farm operating experience, using 10 years of experience as a threshold.

For technology adoption, we selected six technologies as representatives of three categories of PA technologies: georeferencing, diagnostic, and applicative technologies (Wang, Jin, and Sieverding, 2023). Specifically, we included auto-steer and guidance systems (Steer) and automatic section control (SC) under the georeferencing category, satellite and aerial imagery (Imag) and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or drone imagery (Drone) under the diagnostic category, and variable rate application technologies for seeding (Seed) and fertilization (Fert) under the applicative category.

Farmers' Perceptions of Precision Agriculture Technology

Table 1 illustrates farmers' perceptions of PA technology and its potential impact on their farming practices. The findings support the common belief that younger generations are generally more receptive to adopting new technologies. In contrast, older, more established farmers emerge as the most resistant group, a trend consistent with Ofori, Griffin, and Yeager (2020) findings. Age emerges as the primary factor influencing perceptions of PA technology, as younger farmers, both beginners and those already established, are significantly more likely to have a positive outlook on these technologies than their older counterparts. Although senior beginner farmers exhibit a more favorable perception of PA technology than senior established farmers, this difference may be attributed to their lower average age (49 compared to 62). Additionally, experience levels do not influence PA technology perception, reinforcing the idea that age is the dominant factor shaping farmers' attitudes toward these technologies.

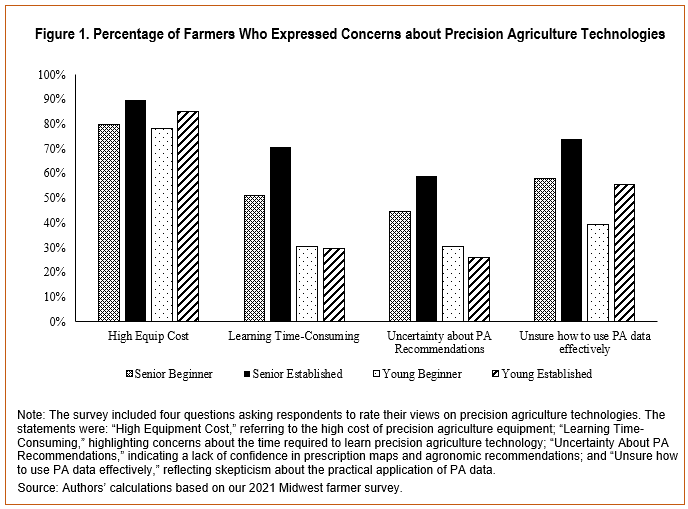

Figure 1 presents the proportion of farmers who agreed with the given statements regarding PA technologies. All respondent groups showed a high level of agreement with the challenges posed by high cost of equipment, with over 78% agreeing to different degrees. While the younger generation was relatively less skeptical than the senior group, higher agreement among established farmers points to experience being more closely tied to this perception than age.

More than 50% of senior farmers agreed with the statement “PA technology is too time-consuming to learn.” Among them, senior established farmers demonstrated the strongest agreement, indicating a greater perception of the learning burden. In contrast, younger generation farmers expressed more confidence in their ability to learn and adopt the technology; only about 30% of young farmers showed the same concern.

For the statement “Not confident in prescription maps and agronomic recommendations,” 60% of senior established farmers expressed a lack of confidence in the data interpretation process. This indicates that senior established farmers generally have lower confidence in interpreting agricultural data. This is probably because they are more inclined to rely on their own experience, particularly when recommendations do not align with their personal judgment. Some senior established farmers may continue to prioritize their own experience over technological recommendations, especially if they are skeptical about the benefits. Conversely, young established farmers demonstrated the highest level of confidence in PA technology, reflecting a greater willingness to trust data-driven decision-making. Given their average age and approximately 10 additional years of experience, it is likely that they began farming around the age of 24 (Table 1). Since most college graduates are around 22–23 years old, many young established farmers may have grown up on farms, attended college, and later returned to their family farms. This finding highlights an interesting trend that farm kids tend to have a highly positive attitude toward adopting PA technologies.

Likewise, for “Not sure how to use PA data effectively” statement, older farmers expressed more doubts about the effective use of PA data. Even among younger farmers, those with more experience were more likely than novice farmers to agree that they were unsure about using PA data effectively. PA technology collects and provides a wide range of data, but as farmers gain experience, they tend to place greater importance on the ability to interpret this information and integrate it into decision-making. This raises concerns that inexperienced farmers may adopt PA technology without fully understanding how to use it effectively. Additionally, these patterns in farmers’ perceptions of PA data use underscores the need to clearly communicate and demonstrate the practical benefits of PA technology while providing technical guidance to encourage its adoption.

Farmers' Likelihood vs. Actual Adoption Rates of Precision Agriculture Technologies

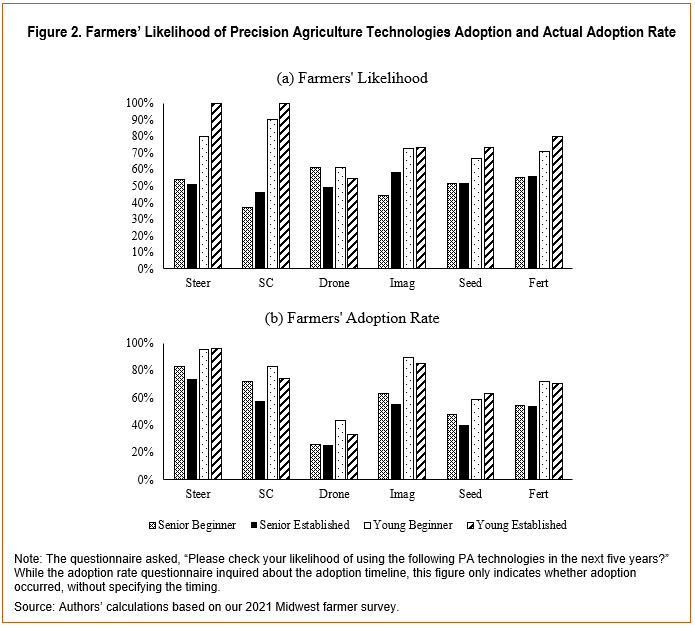

We compared the likelihood of adopting six different PA technologies among different groups of farmers (Figure 2). Consistent with their overall perceptions, senior established farmers were the least receptive to adopting PA technologies, with only about 50% of respondents from this group expressing a willingness to adopt them across all technologies. In contrast, younger farmers demonstrated a likelihood of over 70% for adopting PA technologies, except for Drone technology. Young established farmers showed a greater willingness to adopt PA technologies compared to young beginner farmers. This aligns with the findings in Figure 1. Young established farmers exhibit no hesitation in learning about PA technologies and have confidence in the accuracy of the recommendations provided.

Figure 2 also includes the actual adoption rates of PA technologies. Overall, actual adoption rates are lower than the reported likelihood of adoption within the next 5 years. This gap is unsurprising, as financial constraints often make it challenging for farmers to move from intention to action. The results generally indicate that younger farmers exhibit higher adoption rates compared to older farmers.

Takeaways

This paper examines the influence of age and farm operating experience on the adoption of PA technologies. As commonly believed, younger farmers generally have more positive attitude toward PA technologies (Genius, Pantzios, and Tzouvelekas, 2006). However, our findings suggest that while age is the primary factor influencing adoption preferences, farm operating experience acts as a multiplier. The more experience older farmers have, the more they tend to rely on their existing practices, whereas younger farmers, particularly those who have been farming for over 10 years or grew up on a farm, are more open to learning about and believing in the benefits of PA technologies. Farming experience enables younger farmers to utilize PA technologies more effectively over time. This suggests that PA technologies are essential for the next generation of farmers to continue working on the farm, as they will need to adopt PA technologies to sustain farming with a limited time frame while relying on off-farm employment to increase financial stability.

One of the biggest challenges in adopting PA technologies is cost, a concern recognized by many farmers. Financial support can ease this burden, particularly for young and beginning farmers looking to integrate these technologies. It is crucial to ensure that these farmers adopt PA technologies strategically to stay competitive in the agricultural industry. Katchova and Ahearn (2016) found that young farmers often expand their farms rapidly and invest heavily in new technologies. However, this tendency to invest quickly, sometimes before establishing strong financial management plans, raises concerns. Without proper planning, financial assistance could lead to excessive debt if PA technologies are adopted without a clear strategy for profitability. To enhance young farmers' ability to effectively utilize financial support when adopting PA technologies, educational resources focused on financial planning and risk management should be prioritized.

Our findings highlight the need for further research on how experience, apart from age, influences PA technology adoption and draw attention to the necessity of providing producer support, such as necessary resources and financial knowledge, to promote the successful and sustainable adoption of PA technologies. It is essential to develop financial and educational initiatives that empower young farmers to enter the farming sector and grow, thereby helping address the aging concerns in U.S. agriculture.