Consolidation among ag equipment dealers is an old and ongoing trend. We’ve been reporting on it for decades. In 2009, former Executive Editor Dave Kanicki wrote an article in which he said it was changing the distribution landscape “in ways and by means that many dealers could not have imagined a decade ago.”

In 2020, Farm Equipment hosted a webinar on big ag equipment dealerships in which it was said at the time there were 23 dealer groups having 15-19 stores — an increase of roughly 360% over 2011 — and 24 having 20 or more locations, or a jump of about 300%. The 2023 Farm Equipment 100, published for the first time in the June issue and based upon the 2023 Ag Equipment Intelligence Big Dealer Report, revealed that those biggest dealership groups, the ones with 20-plus stores, have since grown to 30.

One change this rampant consolidation has created is an ever-growing gulf between big dealers and smaller dealers. By that, I mean that bigger dealers are only getting bigger — turning into “mega-dealers,” with small dealers becoming more the exception than the rule.

Such was pointed out to me in a recent conversation I had with the CEO of a 20-plus location John Deere dealership group. He made the point to highlight how leaders of large dealership groups now had very little in common with their counterparts at smaller ag equipment organizations.

What Makes a ‘Big Dealer’

There was a time not so long ago when dealership groups with 5-6 locations made up the largest percentage of the Big Dealer List. When Ag Equipment Intelligence first partnered with George Russell of Machinery Advisors Consortium to publish its annual Big Dealer Report, Russell used 5 locations as the cutoff between big and small dealers. He based his premise in part on an organizational development piece published by the Harvard Business Review entitled, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” by Larry E. Greiner.

The article describes how organizations hit several crisis points in their growth, one of which is based upon organizational size. “A company’s problems and solutions tend to change markedly as the number of its employees and its sales volume increase. Problems of coordination and communication magnify, new functions emerge, levels in the management hierarchy multiply and jobs become more interrelated,” Greiner says. Such crisis points spark the “revolution” cited in the title, which when complete leads to a period of “evolution” in which the company grows until it hits the next crisis point.

The approach makes sense in the way Greiner describes it, and it applies to how dealerships typically grow, whether organically or via consolidation. He calls the first phase in any organization’s development “creativity,” during which leaders communicate with employees infrequently and informally, motivate them with modest salaries and promises of ownership stakes with long hours and hard work and react to customer demands. Such is the approach many an equipment dealership will take in its early days, with the few employees likely being members of the same family or passionate and reliable friends focused more on building something than anything else. Although arguably the “hard work” and “reacting to customer demands” items never change over time, no matter how big a dealership gets.

Crisis Points

The first crisis an organization encounters at this state, Greiner says, is one of leadership, and it comes as the company grows. More employees come aboard, and they require more formal communication. At the dealership level, this is all of the sales, parts and service personnel required in a healthy dealership. Furthermore, these new employees are not motivated by a potential ownership stake, as were the company founders.

New sources of capital are also required, as are more rigid and formal accounting standards — mom coming in a couple days a week to do the books for dad will no longer cut it. “The company’s founders find themselves burdened with unwanted management responsibilities,” Greiner says. “They long for the ‘good old days’ and try to act as they did in the past. Conflicts among harried leaders emerge and grow more intense.”

This is the inflection point Russell identified in dealerships when they hit 5 locations. No longer can dealer principals and their leadership teams run the organization as they had with 1-4 stores. They have to up their game. This inflection point leads to an organization's second phase, called "direction," which requires more structured business management.

I spoke with Russell about the Harvard Business Review article and the increasing gap between big and small ag equipment dealerships. He agrees that the “bigs” are getting bigger, noting that in NAEDA’s 2022 Cost of Doing Business study, the organization had to adjust the total sales volume categories to account for the growing size of dealerships. They had been <$25M, $25-$75M and >$75M. In 2022, the categories became <$50M, $50-$150M and >$150M.

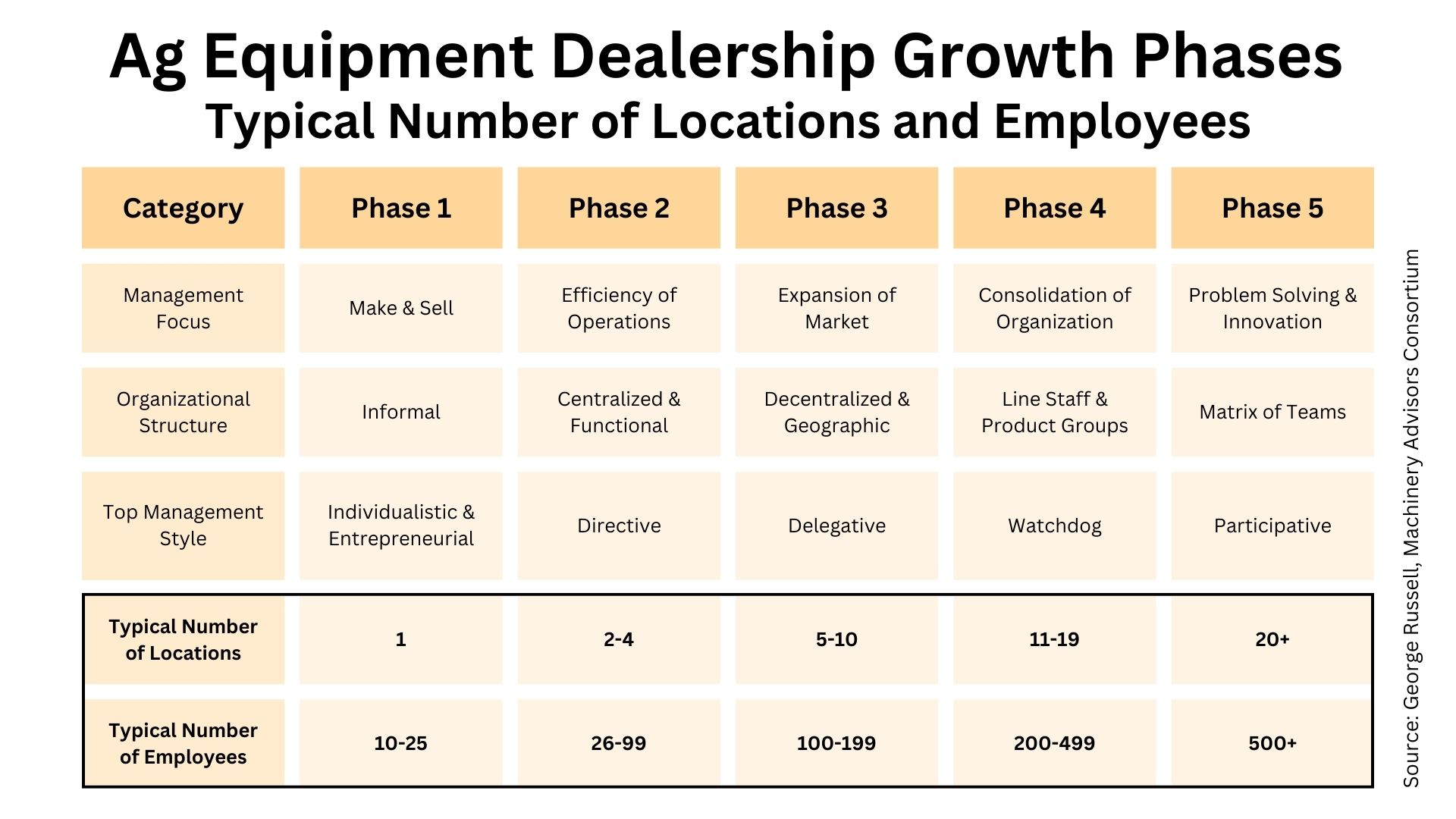

Russell shared the matrix below, which is an adaptation of one published in the HBR piece. He uses this graphic in workshops with dealership management to coach them about how leadership styles change with dealership growth.

Russell says he’s not surprised the dealer I spoke with required a different level of resources, as his company is in Phase 5. Russell is cautious not to draw a hard and fast line between the phases, as he says the items delineating each are intended to be guidelines only. But his point is well-taken.

According to Russell, the 5-location cutoff point for big dealers — which occurs between Phases 2 and 3 — was chosen because it’s the point at which the organizational structure begins to decentralize and the bandwidth available to a single dealer principal is taxed to the point that they need to delegate. Despite big dealers getting bigger, this remains the cutoff point for a dealer to be considered “big,” as dealer principals can no longer go it alone. They require more staff and, in some cases, the services of a consultant in order to move into Phase 3.

He tells me Phase 3 is also the point at which an organization likely needs a full-time human resources manager. Before that phase, leadership personnel are capable of wearing multiple hats and accomplishing a variety of tasks within the organization. But since Phase 3 typically means a company has hit about 100 employees, it’s no longer feasible for several leaders to independently handle hiring, firing, coaching, career development, regulatory compliance, etc. instead of a single person or group doing so for the entire organization.

In fact, Russell explains that one of the hallmarks of organizational growth is increased specialization in job functions. Personnel stop wearing multiple hats in favor of a single one. The example he uses is warranty claims. Someone who handles warranty claims within a large 20+ store dealership group will get up in the morning thinking about warranty claims and spend their entire day doing them — so much so that they get very good at it.

I would encourage you to read the HBR piece and use it and Russell’s matrix to help determine where your dealership is in terms of growth. And let me know — what phase are you in? I’m curious. Use the comment field below!